Blood Simple - Death and Texas

Some directors stumble out of the gate and work their way to later greatness. The Coen Brothers came out of the box a near-complete package.

Fall Focus on Directors - Joel & Ethan Coen

We continue our Fall Focus on Directors with a selection of films from Joel and Ethan Coen, screening all this month at Plaza Theatre.

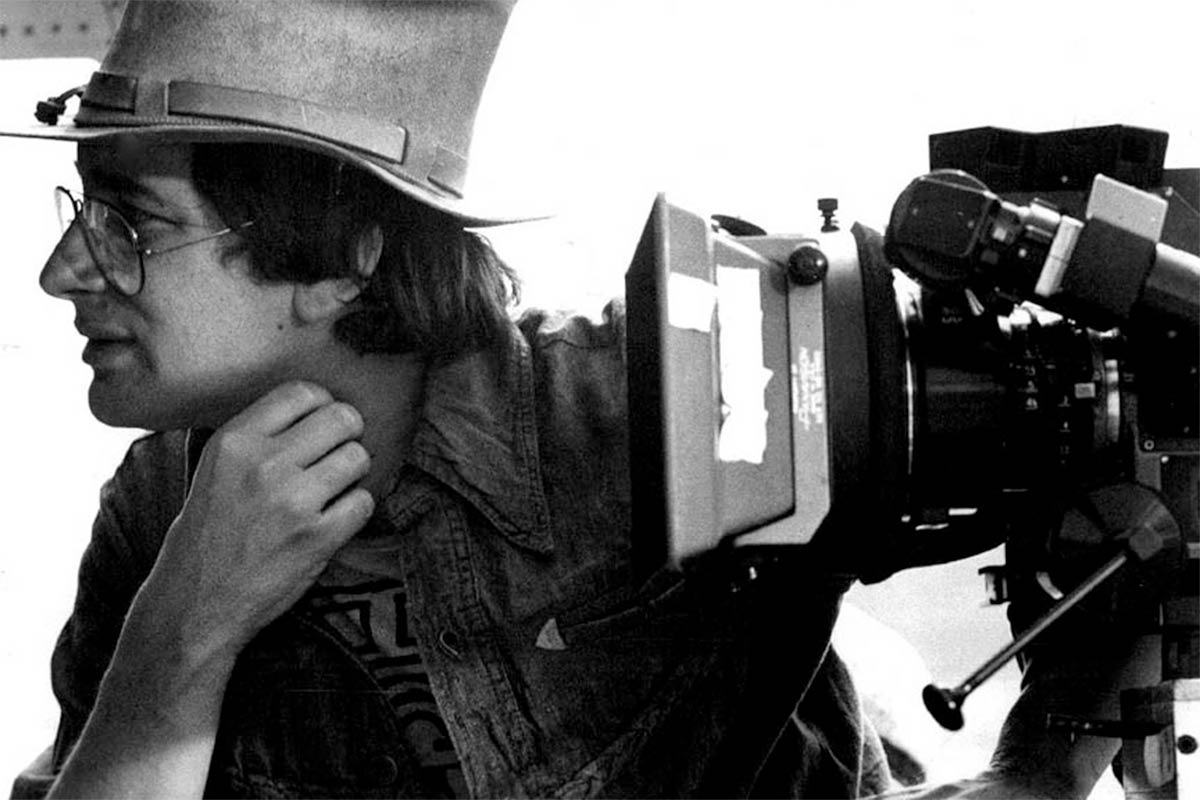

Spielberg at AFI

Steven Spielberg gives a master class in a series of clips from a seminar for film students held shortly after the release of Close Encounters.

Close Encounters: Spielberg Makes Contact

In which Hollywood's Boy Wonder follows up the biggest movie of all time with a more intimate kind of blockbuster, and takes his first step towards more personal filmmaking.